PART 2: Supply Chains are Suffering from Long COVID. Here’s the Vaccine

Global supply chains are still suffering from Long COVID two years after that PCR test came back positive. In Part 1 of this series on the topic, I explained how and why the world is still witnessing COVID-inflicted supply chain interruptions. In Part 2, I follow up with a set of strategies—a vaccine of sorts—to help make supply chains more robust in a disruptive event.

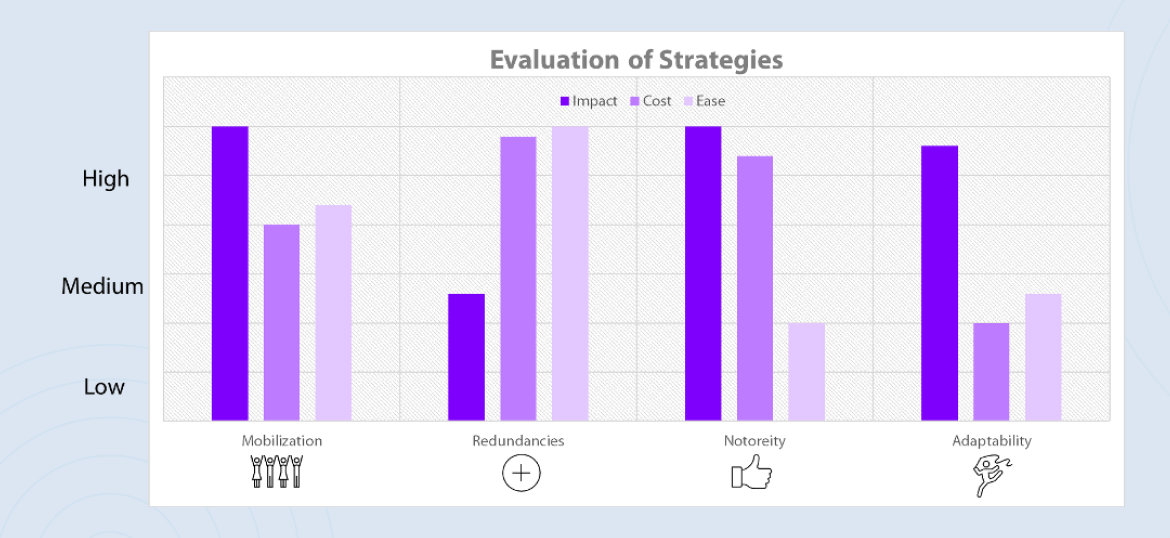

In keeping with the parlance of our times, let us refer to our four-course regimen as an mRNA [sic] vaccine, denoting immunity-boosting jabs targeting Mobilization, Redundancies, Notoriety, and Adaptability. In this text, I elaborate on each of these strategies, providing examples along the way. I also offer an empirical evaluation of each strategy’s expected impact, cost, and ease of implementation.

Mobilization

At the heart of every great endeavor are the people and the technologies empowering them. It should come as no surprise then that building a robust supply chain starts with an elevated preparedness level in personnel and systems. This is achieved along two dimensions: first, horizontally across the supply chain’s different entities. Second, vertically along the org structure of each of those entities.

Preparedness starts with mobilizing staff for the eventuality of a disruption. It involves investing in their ability to identify a disruptive event at an early stage—the objective here is to avoid or contain negative repercussions to the flow of goods while the worms are still in the can. It also entails the creation of contingency plans, or Plan Bs, that allow for the stabilization and recovery of performance after the fact.

Earlier, I wrote about how the automotive industry is still reeling from COVID-related microchip shortages, the chips being a key component in car manufacturing. Automakers are suffering worldwide, but not Toyota, which continues to meet its sales targets. How so? Japan’s 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami led to massive disruptions to Toyota’s supply chain. This led to the company investing heavily in conditioning every element of its supply chain for disruption, starting with the people. In the words of industry expert Christopher Richter, "Toyota learned the lessons of the 2011 earthquake probably better than anybody.” The case of Toyota proves beyond any reasonable doubt that being prepared pays off.

Other key elements to successfully mobilize for disruption include improving the flow of information to smooth out the bullwhip effect and protecting systems from cyberattacks.

A plethora of readily available methodologies come in handy when managing for preparedness. These include Crisis Management & Communication Plans, Supply Chain Risk Plans, Vendor Qualification Tools, and Natural Disaster Response Plans.

Mobilizing people and technology as a strategy for improving robustness is easier said than done. Still, it remains among the most potent of the four strategies at our disposal.

Redundancies

The second, more straightforward jab for building robustness is the creation of redundancies at every critical juncture of the supply chain. A critical juncture here is defined as any area of operations that could, under strain, result in a bottleneck to the flow of goods.

At the sales and operations level, redundancies can be created by holding buffer stocks to protect against delays in delivering an item to a specific point when and where it is required. This includes carrying excess raw material for production, components for assembly lines, and finished goods for outbound logistics and distribution.

Another way to create redundancies is by deliberately maintaining low asset utilization levels—be it in the workforce, a warehouse, a plant, or a distribution fleet—to protect against significant activity variations along the supply chain. Applying such redundancies at the level of logistics network design can aid in rerouting the flow of goods in a geographically confined event.

Finally, upholding a policy to maintain secondary, geographically dispersed suppliers for critical material can help if a supply partner defaults against delivery commitments. For example, Ikea, the Swedish-founded furniture company with a 12,000-item product catalog, uses wood as one of its three base ingredients (plastic and metal being the other two). The company sources wood from dozens of (redundant) suppliers from over 50 countries. Despite this expansive network of suppliers, you will not find a tropical cocobolo hardwood desk or a Brazilian cherry-wood chair on sale. Why not? The purpose of the network is redundancy and flexibility rather than variety. The logs Ikea sources—be it pine, beech, or birch—all meet the exact specifications for their processing into the same Medium Density Fiberboard (MDF).

While creating redundancies across the supply chain is straightforward to implement, it is bound to be the most expensive strategy in any one organization’s repertoire. This is due to the costs incurred by maintaining unused capacity. Its effectiveness is also limited to countering short-term disruptions.

Notoriety

The third jab targets the building of a reputable brand name. While this strategy has a limited effect on avoiding or containing an event, its potency is second-to-none in steadying the ship and returning to expected performance levels. Banks, suppliers, and mostly anyone are more likely to step in to help when an organization’s reputation is intact.

Notoriety is attained by building the brand or trademark, an effort best left to our colleagues in marketing. But it can be furthered by basing all interactions with suppliers (and stakeholders in general) based on shared values and high levels of professionalism. Finally, supporting a culture of innovation and distributing power down to front-line workers further adds to an aura of credibility that supply chains can benefit from.

Converse, Lego, Nintendo, Starbucks, and Polaroid are all household names that experienced a rise and fall. However, what makes them unique is that a revival tailed every fall. Polaroid—a company with a product as archaic as a camera spitting out printed photos—achieved its revival despite two bankruptcies and six CEO changes since its fall. The credit for this feat goes primarily to the equity consumers and investors attached to the brand.

Adaptability

Finally, a robust supply chain is one that is highly adaptable. It is nimble, malleable, and can be twisted and turned to weather any storm.

Three notable stratagems come in handy toward achieving adaptability. One is the standardization of processes and raw materials (as Ikea does) across geographic sites. This allows for seamlessly redirecting the flow of goods in case of disruption at any one node.

Another involves designing products for maximum postponement, meaning the finishing touches to a manufactured product are made-to-order. Consider the case of a painkiller tablet. A pill may be sold in over 400 different packaging models depending on customer requirements (think packaging material, design, number of pills per pack, language on the box, FDA requirements by country, etc.) Rather than produce 400 SKUs to stock, the pharma industry has learned to postpone the decision on packaging until after an order is received. This reduces supply-demand variations, in turn improving customer satisfaction and reducing inventory costs.

A third, more costly lever for achieving adaptability involves maintaining alternative transportation modes as a backup. Flat tire? No problem, the train arrives in 12 minutes.

The impact of supply chain adaptability on business continuity is enormous. Associated costs typically decrease as organizations learn to factor in logistics and the supply chain during the product design process.

There you have it, a 4-course vaccine to ease those lingering Long-COVID symptoms!

Related Articles

PART 3: Supply Chains are Suffering from Long COVID. This is what they’ll recover to look like

Supply chains, too, have escaped with their lives, having contracted Long…

Supply Chains Are Suffering from “Long COVID”. Here’s Why and What to Expect Next

Two years after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the world still reels…

Business in the Time of COVID-19

The cat is out of the bag. One way or another, the novel coronavirus outbreak…

No Cheese, Please! Balancing Flexibility and Efficiency in Supply Chains

Don’t get me wrong, I love Thai food. But having spent the best part of…