The Tyranny of the Loyal versus the "Profits" Dimension

The Tyranny of the Loyal versus the ‘Profits’ Dimension

It was a very sad day, the day I lost my innocence; I remember it vividly, sitting in my cubicle pouring through endless reports when I was shocked into horrible comprehension: Our largest and most loyal customer, the one we loved above all else, was also our very worst customer dragging our profitability down like a pebble in a pond. It felt like betrayal but the brutal reality had to be faced. The long honeymoon our companies enjoyed was in jeopardy.

Several significant issues immediately popped up: First, how could it be that the one we loved most came also to be such a profits’ sinkhole? Second, could a systematic approach be developed to monitor such risks with all customers? And third, what can we do with such knowledge? Could a valid customer strategy be based on what we learn from such monitoring?

Before addressing these issues let me briefly describe the setting: I was fresh out of college working as marketing coordinator for the regional subsidiary of a multinational corporation. Our objective was to maximize the corporation’s sales in the area and our model was to identify, select and support our local distributors, each specializing in different product groups in the markets under our responsibility.

PDC, Our Lovely Loss-Making Customer

The customer I was investigating (let’s call them PDC for Products Distribution Company), was distributing our most popular line of products in our largest market. Our sales through PDC represented more than ten percent of our total in the region. With several dozen distributors in our portfolio, PDC’s share was hugely disproportionate. This obviously brought PDC all kinds of lavish attention from our company. No PDC request was ever refused.

A few weeks before my ‘loss of innocence’ a routine incident occurred. I had pointed out to my boss that we were losing money on an order we were planning to courier to PDC. The reason for the urgent request was entirely due to some internal PDC hiccup. As a good soldier, but still wet behind the ears, I thought it worthwhile to point-out to my boss the unreasonableness of having our organization carry the extra costs alone. My boss looked at me, with pity in his eyes, and said: “I know about this order and you’re right; it is not profitable. But this is PDC, a strategic customer of ours. This is how we treat our best customers and develop their loyalty. This is a very important lesson; learn it”. And the lesson was: What PDC wants PDC gets!

My own department was so dependent on PDC for top line sales, that we were willing to compromise on profits as long as we got those fat juicy orders. Although unspoken, it was policy that we were willing to breakeven and incur slight losses on certain transactions if they happened to be with our key customers. By securing their continued loyalty they would help us, on an aggregate basis, hit one of our most important targets: top line sales for the whole region.

Customer Profitability and the Nose of the Hound

Traditional analysis through our finance and accounting system could easily show us the total sales value per customer. With a little tweaking we could also get the gross margin (sales value minus cost of goods sold) we were making on those sales. But, actual customer profitability (gross margin less all other costs of servicing the account) would have required too much accounting acrobatics and was not even contemplated. As expected, our sales to PDC were by far the highest and the gross margin, in absolute dollar terms, was comparable to that of much smaller distributors. This was no surprise because PDC was getting special volume discounts and free goods not applicable to smaller distributors. What was not visible was the ‘real’ profitability of PDC. The gross margin figure did not include the costs of all our sales people and engineers visits, the training programs we conducted to their sales and aftersales people, their share of the advertising budget and other exceptional expenses. These were simply not accounted for on a ‘per customer’ basis in a traditional accounting system. I discovered PDC’s loss-making status because I had been assigned a special task related to a joint project we wanted to undertake with this special customer. My job was to identify all costs incurred on behalf of PDC but not visible through our traditional accounting system. It was a tedious affair requiring the investigative powers of Sherlock Holmes and the scent of a hound dog.

Surprise, Surprise: Your Largest Customer May be a Profits Sinkhole

What I had inadvertently glimpsed at was one of the great business surprises of the late 20th century which, to this day, is still very much in vogue. Everybody knows of the 80/20 rule. It can be applied safely to customer revenues: 20% of customers will generate about 80% of revenues. The surprise is that, for the few firms that have measured customer profitability the figures are very different: their top 20% of customers in terms of profitability generate between 150 and 300% of the firm’s total profits*. The implication is that some customers are loss makers bringing the profits back down to the 100% level. The most interesting point is that it is the largest customers that will either be very profitable or very unprofitable. Smaller customers do not carry enough weight to cause an impact. The real effect, positive or negative, comes from the large ones, such as PDC.

Homo Economicus is a Tyrant; Deal with It

It would be wrong to reflexively throw the blame for the loss generating accounts on the customers. The “Rational Human” theory states that people are narrowly self-interested actors attempting to maximize utility as consumers (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homo_economicus). Therefore, it is natural for our customers (which we assume to be rational) to strive to squeeze the best deals. They demand more discounts, free goods and support as long as they feel they can get away with it. Think of how easy it is to spoil a child: The more you give the more the child wants. And one is most likely to give-in when one thinks the customer is important. In our situation PDC were vital to help us achieve our top line target. They were our favorite spoiled child. What had not crossed our mind was that they also were a damaging drain on our profits. Until my unexpected investigation we had never questioned customer profitability; we were relying solely on the sterile standard reports generated by our well-meaning finance department.

However, just like with a spoiled child, one must not give-up easily. Many children are actually very well behaved and the credit has to go to the enlightened parents who have used the right strategies to develop a mutually fulfilling relationship. Customers of course are not children. But, they are also naturally demanding and success will depend on how we manage the relationship.

Customer Loyalty? Sure, but at What Price?

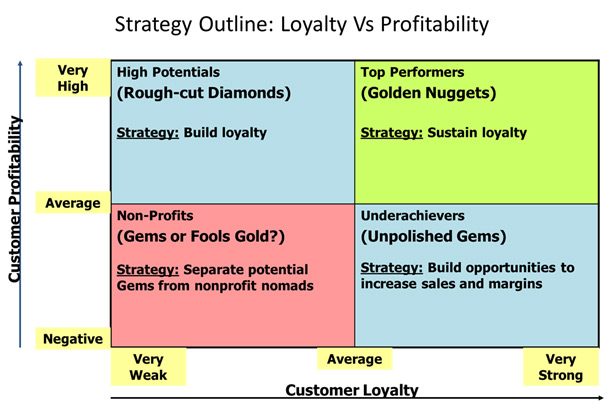

‘Customer profitability’ and ‘customer loyalty’ are both corporate priorities, and the wise manager will strive to find the right balance between them. Several authors have tackled the issue and the well thought-out model below (Best, R. J. (2005).Market-Based Management. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall) is one of those I prefer.

In this model customers are segregated along the loyalty and profitability dimensions in a matrix with four quadrants.

Let’s look at these quadrants one by one.

Underachievers: PDC, our distributor in the case above, is a typical example of customers in the “underachievers” category. They are classified as ‘loyal’ because they keep buying from us and have been with us for a long time. However, due to the choice of their purchases and to the way we have spoiled them with discounts and free support, they are not profitable. Another name for customers in this quadrant is “unpolished gems”, underlining the fact that there-in lies potential. Leveraging the strong rapport we have with these customers we may persuade them to migrate to more profitable offerings (upselling); or, we could reduce our exposure in support of their activities and get them to carry more of the burden; we should also look at our internal processes and develop more efficient ways of providing support.

If we are able to lead these accounts into profitability, the benefits would be enormous since these customers are typically large. However, if all attempts to turn them around fail, then (and the salesman in me is torn at the thought), it may be better to let them go. Thinking about it though, this can be considered a dirty trick we play on our competitors who will now have to deal with these spoiled children.

If you’re interested to know, PDC was successfully turned around and eventually became the customer that generates the most profits for us. They apparently valued our relationship and realized they had as much at stake to stay with us as we had to stay with them.

High Potentials: These customers are profitable but do not buy enough, or often enough, to be considered loyal. These “rough-cut-diamonds” are susceptible to be lost to the competition therefore a special effort should be extended to reinforce the relationship. Our strategy should involve increasing our share-of-wallet (the share of business a company gets from a customer compared to the total spent by this customer). Growing share-of-wallet is more efficient than growing market share and is usually done by offering these customers ancillary and complementary products or services (cross-selling), or by linking them to the company through loyalty schemes of which there are many varieties. Sales and marketing visits as well as relationship building programs are a must.

Non Profits: Customers who are neither loyal nor profitable should never remain long in this category. They are in general new customers testing the water. Extra money and effort was extended to acquire them and it becomes important to segregate the future “gems” from the “fool’s gold”. Some customers’ needs may not be satisfied with our company’s offering and they should not be pursued. These customers are “fool’s gold” and efforts to retain them will result in throwing good money after bad. I also call this category the “transit zone”: A new customer is acquired and typically enters the relationship via this transit zone. But soon, he is either turned profitable or dropped. If the customer remains long in this category it may be an indication of mismanagement. On the other hand, some of these new, not profitable customers may need time and effort to develop into the “gems” of the future. Managed properly they can eventually transform into “golden nuggets” and graduate into our next category.

Top Performers: Customers in this category are the lifeblood of the business. Being profitable and loyal their contribution to the long term success of the firm is essential and the most appropriate strategy is to find new ways to sustain their business. This is done by emphasizing one-on-one relationships, customizing our offerings and developing activities and events that cement our relationship and makes us clearly stand-out as their preferred supplier. CRM (Customer Relationship Management) and loyalty programs were created for these customers.

Our favorite distributor, PDC, after graduating to “top performer” status became the testing ground for several relationship building initiatives. In one of them a team of experts from our company worked with them in order to develop an integrated logistics system that almost transformed them into a seamless extension of our company into their market. Savings in time, effort and money made us reliant on each other ensuring a profitable relationship which lasts to this day. Similar programs initiated with PDC were soon rolled out to our other distributors in the “top performers” category, creating a robust network any competitor could only dream of.

Distributors in this category became like members of an exclusive club. Every year a distributor conference would be held in some resort around the world during which results were discussed, new products introduced, plans made, success stories shared and awards given in a motivating atmosphere that generated positive business results carrying us through to the next event.

Treasure Hunting in Murky Waters

In view of the importance of customer profitability in the articulation of a firm’s customer strategy, it is not surprising that an array of methods is used to capture this concealed metric. While customer revenues can be easily tracked, traditional accounting methods fall short of providing a straight forward approach to allocating costs properly by customer. CRM (Customer Relationship Management) software can be of great help in identifying many elements of the relationship and most firms complement their hunt for customer profitability with in-house developed approaches such as “Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing”.

While by no means simple “Time Driven ABC”, as advocated by many including Robert Kaplan (Kaplan and Anderson, 2003), seems to be one of the best ways of navigating the murky waters leading to a workable understanding of customer profitability. It should be the responsibility of a team, usually led by a marketer, but supported by finance and IT. Their job starts with trying to make sense of how costs are being accrued within the firm by conducting surveys and examining work processes and ends with regular customer profitability reports actively used to define and fine tune the firm’s customer strategy. Committing the firm to “Time Driven ABC” is quite an investment in time and effort, but it is also worth it if used intelligently.

The “Strategic” Customer

Even with irrefutable proof that some customers may be costing you precious profits, a firm may still decide to bite the bullet and maintain them in their portfolio. There may be several reasons for that; some driven by pure ego but, also, some that are rational. A loss-making but known customer may be used as bait to show off and to acquire other profit making customers. Some other times the customer is maintained because the firm is simply keeping them on the back burner while developing a new product, product line or business model that would eventually make that customer profitable. These could be called strategic customers: They may look like loss makers but, in the long run, we will be happy we kept them.

Every time I talk about strategic customers, I can’t help but smile at the thought of another incident involving my boss when we were working on the PDC account. A few weeks after our discovery of the losses and just when the noise they had created was at its peak around our company’s management circles, a clueless colleague of mine tried to justify an expense by innocently claiming it was for the benefit of a “strategic customer”. It was the first time I saw my boss blow his top. Turning red he roared: “Strategic customers? What strategic customers? There is no such a thing as a strategic customer. There are profitable customers and non-profitable customers and that’s that!”

… And that was another priceless lesson I learned.

*It may appear counterintuitive but if we rank a firm’s customers by the amount of profits they generate to the company, the top 20% of these customers will probably contribute, cumulatively, more than the total profits of that firm. The reason this number is larger than the company’s total profits is because, at the tail end of the ranked customers list are some who are loss makers. Every one of these loss-makers chips away at the stash of profits that the top 20% had generated.

Related Articles

Redefining Customer Experience in the Digital Age

Customer experience is the quality of a consumer's interactions with a…

Should organizations allow customers to complain?

In this globalized world competition is fierce at all levels. Segments…

AI, Chatbots and Customer Service

The future of customer service has become a recurring topic in the training…

The Secret: Innovation by Numbers

I have yet to hear about an organization that does not claim to value…